In the late 19th century, at the dawn of the electric age, famous spiritualists traveled the country selling the promise of contact with “the other side.” An interest in unseen, possibly supernatural, energies developed apace with the introduction of electricity, that invisible force illuminating the night and animating formerly lifeless objects. In 2016, I thought of this legacy as I stepped into Timeless Motion, a multimedia exhibition of local moving image artists currently on view at San Francisco’s SOMArts.

The first piece in the gallery is Scott Stark’s Low-Res Arborscope, a wasteland as gray as Dorothy’s Kansas inhabited by a forest of dead tree parts. On one end a projector shoots its images toward slats of wood swinging in a fan’s breeze. The light that spills around the edges of this moving screen generates a force field, a no-go zone created by either the forbidding nature of the lifeless detritus or the perceived inviolability of art in a gallery setting. Whatever the cause and whatever the purpose, one begins to think post-apocalyptically of disasters in the making and what will be left behind.

This piece (though not my favorite in the show) effectively promotes Timeless Motion’s thesis, creating a dead space in the middle of the gallery with clearly permeable borders between past, present and a possible future. The landscape, already harsh, is made more forbidding with the addition of electric light, which both illuminates and defines the installation as a kind of afterlife.

In stark contrast (no pun intended, Scott), Paul Clipson’s 16mm film FUNERA ET SERPENTIUM soothes the eye and calms the nervous system. Clipson works exclusively in celluloid, generating gorgeous multi-colored and multi-layered images with in-camera effects. His world seems populated with visual delight, which he eagerly captures and shares. The warmth of Clipson’s photographic process, even when the imagery is of cityscapes and electric light patterns, fosters an organic feeling, a celebration of human activity that feels positive — a kind of communion with both the natural world and the built environment.

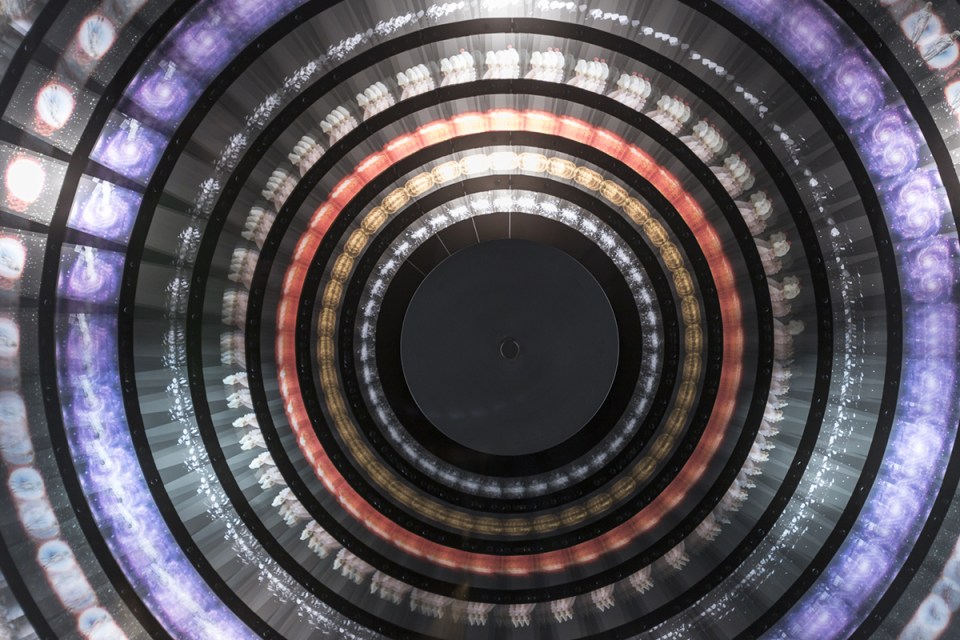

In two other closed-off sections of the gallery, viewers encounter the sublime with Kerry Laitala’s The Retrospectroscope and The Cosmoscope, kinetic sculptures creating mind-bending worlds that threaten to engulf and destroy. Signs warn the viewer to beware of possible seizure-inducing effects before entering into the tiny curtained rooms where dangerous disks (exploded zoetropes, 19th-century inventions that predicted cinema) swirl in front of strobe lights.

The combination of cramped space, swirling motion and flashing lights created instant nausea for me. Laitala’s works offered an experience of beauty ultimately denied (to me) by their own dangerous nature. Another 19th-century allusion came to mind — that of a medicine man offering cures but selling poisons.

Laitala’s other works, called “Cosmo-Electro-photographs” confirm Timeless Motion’s desire to connect electricity and spirituality. A group of large prints resembling mandalas are actually camera-less photos, the result of electrical discharge from etched plates — invisible forces captured, frozen and hung on the wall.

Mark Wilson continues this fascination with pre-20th century signs and symbols in works spread across the walls of the exhibition. Once again referencing the zoetrope in presentation, Wilson’s pieces also concern themselves with ritual images and relics of ancient cultures now rendered silent and unknowable.

Kathleen Quillian’s Expanded View is both a stop-motion animated video (reminiscent of Lewis Klahr, Martha Colburn, and Larry Jordan’s work) and a flat explosion of the images she used to create that animation affixed to the wall. The animated video is frenetic and full of witty juxtapositions, but the static collages trap and dissipate the video’s energy, perhaps in an attempt to reverse the polarity of the exhibition. Where electricity brings the other works to life, Quillian demonstrates how its lack causes a tiny death.

Elsewhere, Keith Evans’ Lenticle to the Sun is an installation built into the floor of the gallery. A phonograph causes bicycle wheels to slowly rotate under a large piece of Plexiglas; a telescope sits on top of the plexi, pointing at a projection high up on an opposite wall. Look through the telescope lens and see a mystery. Perhaps this is always how we ponder the sky; and perhaps Lenticle to the Sun is merely a description of looking, a questioning of the nature of what we see but can never truly know.

The final work in the show, Jeanne Liotta’s Diagram Squared, is equally mysterious. A short video of 1970s scientific animations project onto two inkjet prints. Though the animations were created to demonstrate specific processes, Liotta strips them of their soundtracks and therefore their didactic content. The will to explain is stifled by our inability to comprehend. But what can we know? The universe is in timeless motion, guided by dark matter and unseen forces we may never detect, much less understand.

Timeless Motion is on view through March 23, 2016 at SOMArts in San Francisco. For more information visit somarts.org.